MARTHA’S VINEYARD SIGNED LANGUAGE COMMUNITY: DRIVING TOUR

Hereditary deafness is comparatively rare, but in the township of Chilmark it was common enough, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, to be regarded as a fact of life. Deaf residents of Chilmark were valued members of the community, fully integrated into its political, economic, social, and spiritual life. Hearing residents conversed with their deaf neighbors in Martha's Vineyard's distinctive form of sign language, and used it to sign public gatherings such as town meetings and church services for their deaf friends and relatives. Visitors "from away" were startled by the prevalence of deafness and sign language, but residents saw their deaf neighbors simply as people.

The incidence of hereditary deafness in Chilmark declined in the second half of the nineteenth century, as the town grew less isolated. The Chilmark deaf community consisted, on the eve of World War II, of a handful of elderly individuals born between 1870 and 1890. Nora Ellen Groce's landmark study of the Chilmark deaf, carried out in the early 1980s, relied on informants—by then elderly themselves—who had lived among that last generation of the deaf community in their youth. The last members of the community died in the early 1950s, and more than half of Groce's hearing informants died within a year or two of being interviewed.

There are no monuments to the Chilmark deaf community: no statues raised in its memory, no plaques on roadside boulders, and no meticulously preserved house museums whose interior spaces capture the lives its members led. The land changes slowly, however, and the structures erected on it yield only grudgingly to the ravages of wind, water, and age. Amid the Martha's Vineyard of today, it is still possible to see traces of the Chilmark of the 19th and early 20th centuries: an insular world of small farms and fishing shacks where, in Groce’s famous phrase, “everyone . . . spoke sign language.”

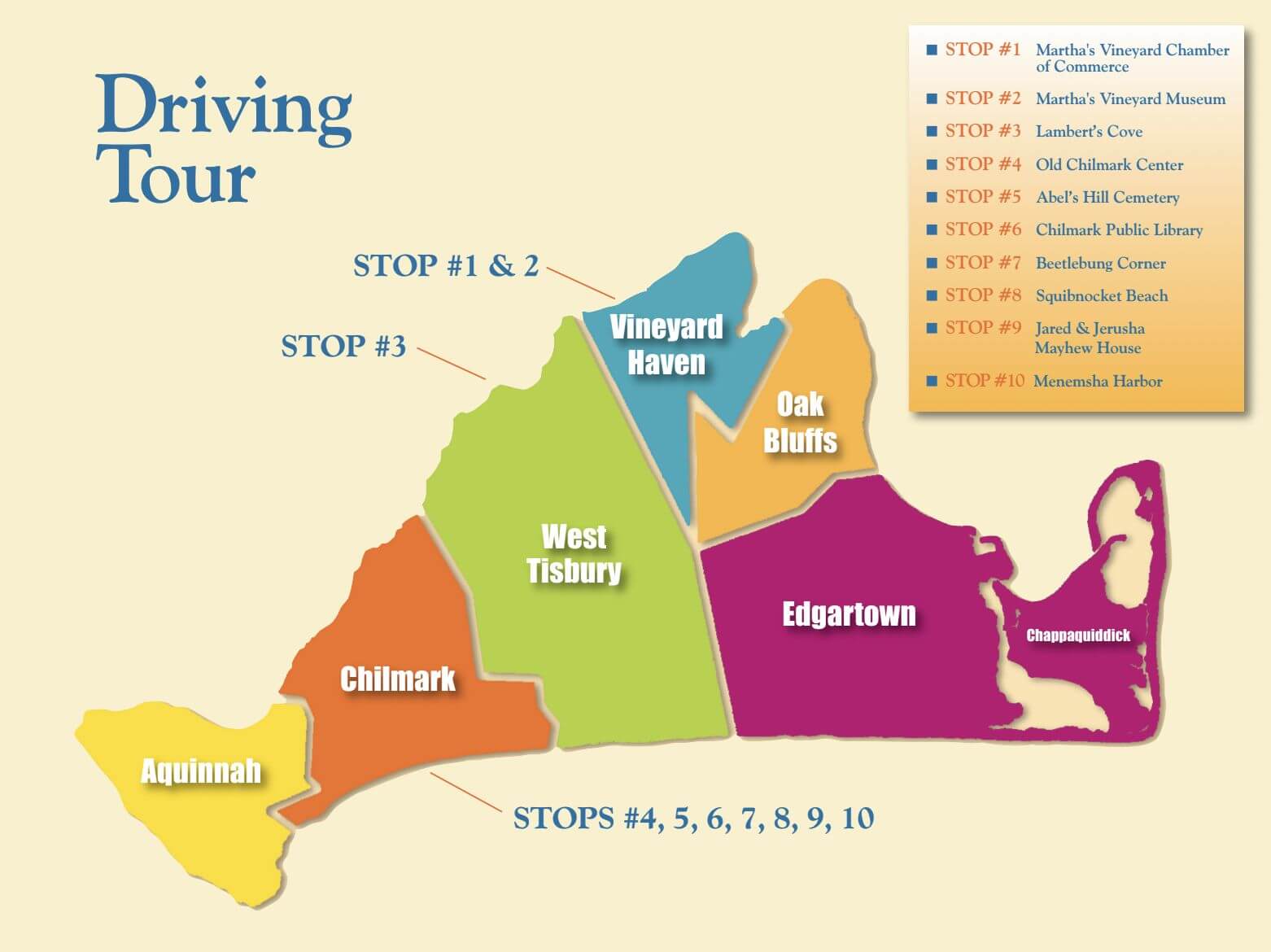

Stop #1: Martha's Vineyard Chamber of Commerce

24 Beach Street, Vineyard Haven

Beach Street, which runs in front of the Chamber of Commerce building, was once the gateway to the village of Holmes Hole. Until the 1830s, a 6-foot-deep channel called Bass Creek flowed where Water Street and Lagoon Pond Road run today, and the sail-powered ferries from the mainland docked the foot of Beach Street, where the Five Corners intersection is today.

Judge Samuel Sewall, whose account of a 1714 visit to Martha's Vineyard contains the first mention of a deaf resident of the Island, began his journey at Beach Street. So, perhaps, did Jonathan Lumbert (the deaf man he met), when he immigrated to the Island around 1700.

Stop #2: Martha's Vineyard Museum

151 Lagoon Pond Road, Vineyard Haven

Located on a hilltop overlooking Lagoon Pond and Vineyard Haven Harbor, the Museum preserves, exhibits, and interprets materials related to the history and culture of Martha's Vineyard . . . including the Chilmark deaf community.

Thomas Hart Benton's portrait of Joseph "Josie" West, a deaf farmer from Chilmark, is on permanent display in the "One Island Many Stories" gallery. Other materials related to the Chilmark deaf community, including a notebook kept by Alexander Graham Bell during his investigations on the Island in the 1880s, are available for viewing in the Museum library. For directions and hours see www.mvmuseum.org

Stop #3: Lambert's Cove

281 Lambert's Cove Road, West Tisbury

Jonathan Lambert (or Lumbert), who immigrated to Martha's Vineyard from the English county of Kent around 1700, is believed to have been the ancestor of all the hereditary deaf residents of Martha's Vineyard. He settled near a shallow cove on the north shore of the island, which now bears his name.

The land on which Lambert and his children settled remains in private hands, but the cove, with its crescent-shaped white-sand beach, is public. The parking area, which is restricted to West Tisbury residents and their guests during the summer months, is linked to the beach by a quarter-mile trail and boardwalk.

Stop #4: Old Chilmark Center

Middle Road, junction of Tea Lane and Meetinghouse Road, Chilmark

Until the early 1900s, the village center of Chilmark stood at these crossroads. Deaf residents of the town would have come here to worship at the Congregational and Methodist Churches, do business or socialize at one of the two general stores, or attend meetings at the Town Hall.

The roads that converge here all date to the 1700s. Most deaf citizens of Chilmark would have spent their lives on widely scattered farms like those that, even today, border Middle Road. The distinctive "dry stone" walls bordering the fields were created by stacking stones dug out of the fields to make plowing easier.

Stop #5: Abel's Hill Cemetery

322 South Road, Chilmark

Abel's Hill, named for 17th-century Wampanoag resident Abel Wauwompuhque, was the site of the first two Congregational meetinghouses in Chilmark, around the town's principal cemetery. The old section of the cemetery is located at the top of the hill, behind the parking area and directly ahead of you as you drive in.

At least twenty-eight members of the Chilmark deaf community are buried on the hilltop, including Jared and Jerusha Mayhew (Stop #9), "One-Armed Ben" Mayhew, Josie West (Stop #2), George and Dedamia West (Stop #8) and Katie West (Stop #6).

Stop #6: Chilmark Public Library

South Road, junction of Middle Road and Menemsha Crossroad, Chilmark

Founded in 1882, the library was originally located in E. Elliot Mayhew's store, and then in the town hall. In 1953, the town purchased the home of the late Katie West— sister-in-law of George and Josie West (Stop #8) and the last native speaker of Martha's Vineyard sign language—who had died the year before. The library opened in its new home in 1956.

Stop #7: Beetlebung Corner

South Road, junction of Middle Road and Menemsha Crossroad, Chilmark

E. Elliot Mayhew moved his general store, which doubled as the post office, to the site of the current Chilmark Store. A new town hall, still in use today, was built on the Middle Road side of the intersection in 1887, and the

Methodist church (now the Chilmark Community Church) moved to the Menemsha Crossroad in 1910. These changes completed the shift of Chilmark’s village center from its old location (Stop #4) to its current one.

Stop #8: Squibknocket Beach

Squibnocket Road, off State Road, Chilmark

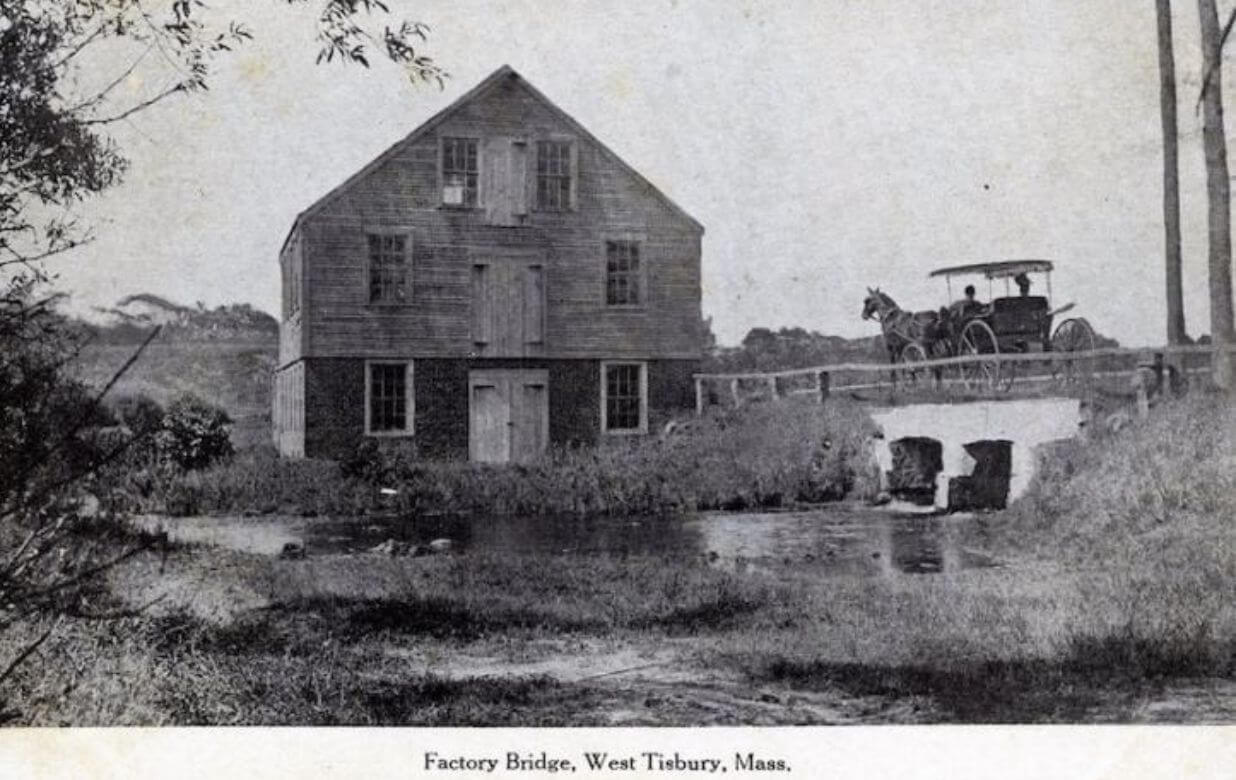

The town of Chilmark has no natural deep-water harbor, but in the 18th and 19th centuries, many Chilmark fishermen used Squibnocket as a base of operations, launching their small boats from the beach in the morning and pulling them above the reach of the tide at night.

The tiny post office at Squibnocket was overseen by a local farmer, George West. His wife, Dedamia Tilton West, was deaf, as were five of the couple's eight children—among them Josie West (Stop #2) and George West, Jr. (the subject, along with his wife Sabrina, of Thomas Hart Benton's painting "The Lord Is My Shepherd"

Stop #9: Jared & Jerusha Mayhew House

251 State Road, Chilmark

Nearly hidden from the street by high hedges, this turreted Queen-Anne-style house is recognizable by its yellow-painted clapboards, white trim, and red roof. Built in the late nineteenth century, it was the home of Jared Mayhew, his wife Jerusha, and (until her marriage in 1898) their daughter Ethel Love Mayhew.

A prosperous farmer who ran sheep on over 100 acres of land, Jared—like his parents Benjamin and Hannah, his older brother Benjamin, his uncle Alfred, and his aunts Ruby and Love*—was deaf. He is said to have been the last Chilmark resident born into a family where deaf children outnumbered hearing ones.

Stop #10: Menemsha Harbor

Basin Road, Chilmark

Before 1900, Menemsha Harbor was the site of a much smaller settlement known as Creekville.

The present-day fishing village of Menemsha began to grow after 1900, when a shallow, meandering tidal creek was deepened to form a channel and an anchorage dredged alongside it.

Chilmark residents travelling to New Bedford often departed from Menemsha, riding with friends or family members going to "The City" to bring fish and other products to market, or buy supplies.

Many of the deaf children who left the Island to be educated at the American School for the Deaf likely took their first steps away from home on these shores.