HISTORY OF MARTHA'S VINEYARD

The earth here tells the story erased elsewhere in New England. The Aquinnah Cliffs lay bare to geologist the history of the past hundred million years. Traveling the South Road to Aquinnah, one goes over low hills and valleys cut by streams that ran off melting glaciers at the end of the Ice Age. The first humans probably came here before the Vineyard was an island. It is thought that they arrived after the ice was gone, but before the melting glaciers in the north raised the sea level enough to separate Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket from the mainland. Native American camps that carbon-date to 2270 B.C.E. have been uncovered on the Island. The Wampanoag people have lived for thousands of years on the island of Martha’s Vineyard.

“Wampanoag” means “People of the First Light.” Before Bartholomew Gosnold renamed the island Martha’s Vineyard in 1602, it was called Noepe by the Wampanoag, meaning “land amid the waters.” Many Wampanoag still live on ancestral lands located on the southwestern end of the Island on the 3,400-acre peninsula known as Aquinnah. At present, there are over 900 members listed on the Tribal rolls. Of these, approximately 300 reside on Martha’s Vineyard.

The Island's colonial period was marked by prosperity as well as peace. The sea provided fish for both export and Island use, and the Wampanoags taught the settlers to capture whales and tow them ashore to boil out the oil. Farms were productive as well; in 1720 butter and cheese were being exported by the shipload. The American Revolution, however, brought hardships to the Vineyard.

Despite the Island’s declared neutrality, the people rallied to the Patriot cause and formed companies to defend their homeland. With their long heritage of following the sea, Vineyarders served effectively in various maritime operations. On September 10, 1778 a British fleet of 40 ships sailed into Vineyard Haven harbor. Within a few days the British raiders had burned many Island vessels and removed more than 10,000 sheep and 300 cattle from the Vineyard. The raid was an economic blow that affected Island life for more than a generation. The whaling industry did not engender a real recovery until the early 1820s, when many of the mariners built their beautiful homes in Edgartown.

The Civil War brought an end to the Golden Age of Whaling. Ships on the high seas were captured by the Confederate Navy, while others were bottled up in the harbors. Either way, it meant financial ruin for the ship owners and the Island. In 1835 a new and enduring industry was born when the Edgartown Methodists held a camp meeting in an oak grove high on the bluffs at the northern end of the town. The worshipers and their preachers lived in nine improvised tents and the speaker’s platform was made of driftwood. The camp meeting became a yearly affair and one of rapidly growing popularity. Many found the sea bathing and the lovely surroundings as uplifting as the call to repent. The Methodist Campground meetings were the catalyst that transformed the Island from a simple farming community into an internationally known seaside resort by these first groups of tourists.

Many who came for a week or two eventually rented houses and later became property owners – a pattern that still occurs today. Summer visitors become seasonal or, as in the case of many writers and artists, year-round residents. These people, along with the many who retire to the Vineyard bring the world to the Island much as the far-traveled captains did in the great days of whaling.

Many who came for a week or two eventually rented houses and later became property owners – a pattern that still occurs today. Summer visitors become seasonal or, as in the case of many writers and artists, year-round residents. These people, along with the many who retire to the Vineyard bring the world to the Island much as the far-traveled captains did in the great days of whaling.

Many year-round residents of Aquinnah are descendants of the Wampanoag tribal members who showed the colonial settlers how to kill whales, plant corn, and find clay for the early brickyards. Much later, these Aquinnah Wampanoaq were in great demand as boatsteerers in the whaling fleets. It was the boatsteerer who cast the iron into the whale. The Aquinnah Wampanoaq were judged to be the most skillful and courageous boatsteerers of that era. The courage of the early residents of Aquinnah demonstrated itself in the many instances when they took to the seas in deadly weather to aid survivors of wrecks that took place off the Aquinnah Cliffs. As further testament to their valor, a plaque on the schoolhouse commemorates the fact that Aquinnah sent more men, in proportion to its size, to fight in World War I than did any other town in New England.

The brilliant colors of the mile-long expanse of the Aquinnah Cliffs astonished early explorers and have continued to be a source of intense interest to scientists and visitors alike. Here layers of sand, gravel, and clay of various types and hues tell a hundred-million year-old story of a land first covered with forests, then flooded and laid bare, then covered with new growth, time and again. The seas, glaciers, and land itself have contorted these once-level layers into waving bands of color that stream above the sea. Erosion continues as it has for centuries, turning the seas red and revealing fossil secrets. From the fossils revealed by erosion we know of the great sharks that swam over what is now Chilmark, of the clams and crabs that inhabited the ancient ocean. Pieces of lignite from the Cretaceous period are found on the beach, looking like nothing so much as the remnants of recent campfires. Fossil bones of camels and wild horses, as well as those of ancient whales, have been found in the Cliffs. The Aquinnah Cliffs are a national landmark; yet they are seriously threatened by erosion. To protect the Cliffs, climbing and the removal of clay are both prohibited by law.

Because of the extremely dangerous rocky ledge offshore, the seas around Aquinnah have always been a place of great peril to the mariner. One of the first revolving lighthouses in the country was erected atop the Cliffs in 1799. It had wooden works that became swollen in damp or cold weather, when the lighthouse keeper and his wife would be obliged to stand all night and turn the light by hand. The current red-brick, electrified Gay Head Light stands in its place.

Chilmark is a town of rolling hills and unmatched coastline. Not so long ago uninhabited except for an occasional farm or fishing village, it now provides the setting for many a summer home. The stone fences of the sheep farms still ribbon the hills, while the old stone animal pound stands on the South Road, a reminder of the days when a gate left open resulted in a roaming flock and a fine for its owner. The center of Chilmark boasts a lovely church. The unique pointed steeple was added when the building was moved in 1915 from its original site on Middle Road. All roads from the center at Beetlebung Corner lead to points of beauty. Middle Road, perhaps the most pastoral of Island roads, provides a lovely view of a placid farm with the Atlantic Ocean as a backdrop.The Menemsha Crossroad joins North Road and takes one to the fishing village once known as Menemsha Creek. Here the draggers still come in with their great nets and the lobstermen land their catches. Seafood may be purchased on the spot. Lovely private vessels lie along the docks while yachtsmen take on fresh water and supplies. A safe public bathing beach is another attraction. Menemsha is also the home of a Coast Guard station.

Before the days when the Coast Guard looked out for shipwrecked vessels, Vineyarders took it upon themselves to form volunteer groups that provided assistance to sailors in times of need. Open dories were launched into the stormy seas from Squibnocket Landing, the only beach on the South Shore shallow enough for a boat to be launched or landed in heavy weather. It is now a beach for year-round and summer Chilmark residents.

One of New England’s most elegant communities, Edgartown was the Island’s first colonial settlement and it has been the county seat since 1642.The stately white Greek Revival homes built by the whaling captains have been carefully maintained. They make the town a museum-piece community, a seaport village preserved from the early 19th century. Main Street is a picture-book setting with its harbor and waterfront. The tall square-rigged ships that sailed all the world’s oceans have passed from the Edgartown scene, but the heritage of those vessels and their captains has continued. For the past hundred years Edgartown has been one of the world’s great yachting centers. To view and appreciate this town fully, you must walk its streets. North Water Street in particular has a row of captains’ houses not equaled anywhere. Study the fanlights and widows-walks by day and stroll the streets after the lamps are lit.South Water Street is dominated by a huge pagoda tree brought from China as a seedling by Captain Thomas Milton in the early days of the 19th century. The house beyond it was that of Captain Valentine Pease, on whose ship Herman Melville made his only whaling voyage.

Many homes in Edgartown predate the whaling era. Most are private residences, but three notable ones are serving other needs. Both the Vincent House (built in 1672, is the oldest known house on the Island) and the Thomas Cooke House are now museums. At 34 South Summer Street, you’ll find the home built by Benjamin Smith in 1760. It is now the office of the Vineyard Gazette.

Across from the Gazette is the Federated Church, built in 1828. It still has the old box pews, which are entered through little doors and have narrow seats around three sides.

The famous Old Whaling Church with its six massive columns commands Main Street. Built in 1843 at the height of the Whaling Era, the Church was given to the Martha’s Vineyard Preservation Trust in 1980. It has been transformed into a performing arts center. Next door is the Dr. Daniel Fisher House, built three years before the Old Whaling Church.

There are excellent public beaches in the township of Edgartown. Norton’s Point, known as Katama, is a barrier beach providing surf bathing and the opportunity to explore Katama Bay on the other side of the dunes. Wasque and Cape Poge on Chappaquiddick are both unspoiled areas owned and maintained by The Trustees of Reservations. They are favorite spots for bluefish and bass fishermen. Lighthouse Beach, located off North Water Street near the town center, offers calm water and views of harbor activities. Bend-in-the-Road Beach, part of Joseph Sylvia Beach, has ample parking and is accessible by bicycle trail.

Felix Neck is about three miles outside the center of town on Edgartown-Vineyard Haven Road. The 200 acres, owned by the Massachusetts Audubon Society, provide marked trails and a program of wildlife management and conservation education throughout the year.

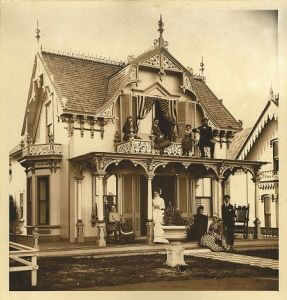

In 1835 this community served as the site for annual summer camp meetings when Methodist church groups found the groves and pastures of Martha’s Vineyard particularly well suited to all-day gospel sessions. Wesleyan Grove, as the Oak Bluffs Campground was called, rode the crest of the religious revival movement. By the mid-1850s the Sabbath meetings here were drawing congregations of 12,000 people. They came for the sunshine and sermonizing in hundreds of individual church groups. Each group had its own communal tent where the contingent bedded down in straw purchased from local farmers. Services were held in a large central tent. The communal tents gave way to “family tents,” which reluctant church authorities granted only to “suitable” families. But the leisure urge could not be checked. Family tents turned into wooden cottages, designed to look like tents. And the cottages multiplied, trying to out-do each other in brightly painted fantasies of gingerbread patterns reflected in the carpenter gothic trim. A new all-steel Tabernacle structure replaced the big central tent in 1879; it stands today as a fine memento of the age of ironwork architecture and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.Within 40 years of the first camp meeting here, there were crowds of 30,000 attending the Grand Illumination that marked the end of the summer season with a glorious show of Japanese lanterns and fireworks.

Wesleyan Grove struggled to hold its own against such secular attractions as ocean bathing, berry picking, walking in the woods, fishing, and croquet playing. There were efforts to ban peddlers, especially book peddlers. A high picket fence was built around the Campground proper. By the 1870s, Wesleyan Grove had expanded into Cottage City and Cottage City had become the town of Oak Bluffs, with more than 1,000 cottages.

Steam vessels from New York, Providence, Boston, and Portland continued to bring more enthusiastic devotees of the Oak Bluffs way of life. Horse cars were used to bring vacationers from the dock to the Tabernacle. The horse cars were later replaced by a steam railroad that ran all the way to Katama. One of the first passengers on the railroad was President Ulysses S. Grant. The railroad gave way to an electric trolley from Vineyard Haven to the Oak Bluffs wharves, and the trolley eventually gave way to the automobile.

Oak Bluffs is also the home of the Flying Horses Carousel, the oldest continuously operating carousel in the country. Its horses were hand-carved in New York City in 1876. This historic landmark is maintained by the Martha’s Vineyard Preservation Trust. It is open daily during the summer, and on weekends in the spring and fall.

Excellent shops, fine restaurants, and a beautiful harbor are only a few of the attractions that make Vineyard Haven so special to tourists and residents alike.The town that incorporates Vineyard Haven is called Tisbury, after a parish in England near the birthplace of the Island’s first governor, Thomas Mayhew. English settlement of the area dates from the mid-1600s, when Mayhew purchased the settlement rights from the Crown. Owen Park, off Main Street (just beyond the shopping district), is named for William Barry Owen, who made his fortune as the owner of the rights to Thomas Edison’s 'Talking Machine' (popularly known as the Victrola). Following his death, his widow donated the land on which Owen Park now rests to the town. The adjoining beach is a fine place to watch the harbor. Ferries shuttle in and out, providing the Island’s year-round connection to the mainland. On the opposite side of Main Street from Owen Park is the Old Schoolhouse Museum. Erected in 1828, this building has served many uses. It was once a carpentry shop, a school, and later served as the Congregational Church. In front of the former Museum stands the tall white Liberty Pole, commemorating the daring of three young women who inserted gun powder in the base of the town’s liberty pole in 1778 and blew it up to keep it from being used as a spar by a British warship.When the Congregationalists outgrew their little church in 1844, they built a neo-classic building on Spring Street that later became the Unitarian Church and eventually the town hall. Vineyard Haven’s municipal building is one of the Island’s most handsome architectural legacies of whaling days. It also houses the Katharine Cornell Theatre, a legacy gift to the town in which she summered for many years. The walls of the second story theater are hung with murals depicting the seasons by renowned local artist Stan Murphy.

Just blocks away, The Vineyard Playhouse building on Church Street was built in 1833 as a Methodist meeting house. Today it houses the Island’s only year-round professional theater company.

When ships were powered by wind and canvas, Vineyard Haven was one of New England’s busiest ports because of its strategic location on the sailing routes. Most of the coastwise shipping traveled through Vineyard Sound (13,814 vessels were counted in 1845). Holmes Hole, as this harbor community was called, provided a convenient anchorage. Here a ship and its crew could lay over comfortably to wait out bad weather, pick up provisions, or take on an experienced local pilot who could negotiate the rips and shoals that were the special perils of this sea route.

In addition to Owen Park, the town maintains War Veterans’ Memorial Park off Causeway Road and visible from the parking area on Beach Street.. The park includes playground equipment for young children and playing fields used by local ball teams.

There are many scenic places around the town: in addition to Main Street and the harbor, the Tashmoo Lake overlook on State Road, the nearby Tisbury Water Works, West Chop Lighthouse, and the area around the drawbridge on Beach Road are favorite spots for photographers.

It was the mill site that originally attracted settlers, because there was no stream in Edgartown strong enough to dam for a water wheel. The grist mill gave way in 1847 to the manufacture of satinet, a heavy fabric for whalemen’s jackets made from Island wool. The Congregational Church on State Road is always open to visitors. Solid and settled as it now looks, even this structure did not escape the Islanders’ penchant for moving buildings around. The original churchyard, where the first settlers of the town are buried, is about a quarter of a mile down the road. Near the church is the West Tisbury Town Hall. Several old homes here started out as inns, back when a trip from the down-Island ports to Aquinnah or Chilmark was a long haul over sandy roads. Daniel Webster stayed at a house nearby and across the little pond from the old inn is the site of a house built by Miles Standish’s son in 1668.

The largest homes in town were owned by sea captains, and some of the finest are still occupied by their descendants. Several captains’ houses can be found on Music Street, given its name after a number of its families purchased pianos with new whaling money.

The Lambert’s Cove settlement has its share of fine homes and a charming white church. The Cove was once a place of anchorage for the town of West Tisbury. The area housed clay works, salt works, and extensive trap-fishing operation. All this has vanished. Even the road to the harbor is gone. A woodland path leads to the beach, which is now set aside for year-round and summer residents of West Tisbury.

Other points of interest are Cedar Tree Neck Nature Preserve, the Polly Hill Arboretum, and the Christiantown Memorial.

Cedar Tree Neck offers unspoiled woods, with a freshwater pond and brooks, bounded by North Shore Beach. Picnics, fishing, and bathing are not permitted, but there are marked trails for those who enjoy the opportunity to watch birds and walking.

The Arboretum contains more than 200 species of trees, a picnic area, and Visitors’ Center. A complete description appears in the Conservation and Recreation section.

The Christiantown Memorial is located off Christiantown Road. Here one may see a tiny chapel, a pulpit rock where services were held for the Wampanoag in the 17th century, the rough small burial stones of these first converts, and a nearby wildflower garden.